What Is the Genetic Fallacy? | Definition & Examples

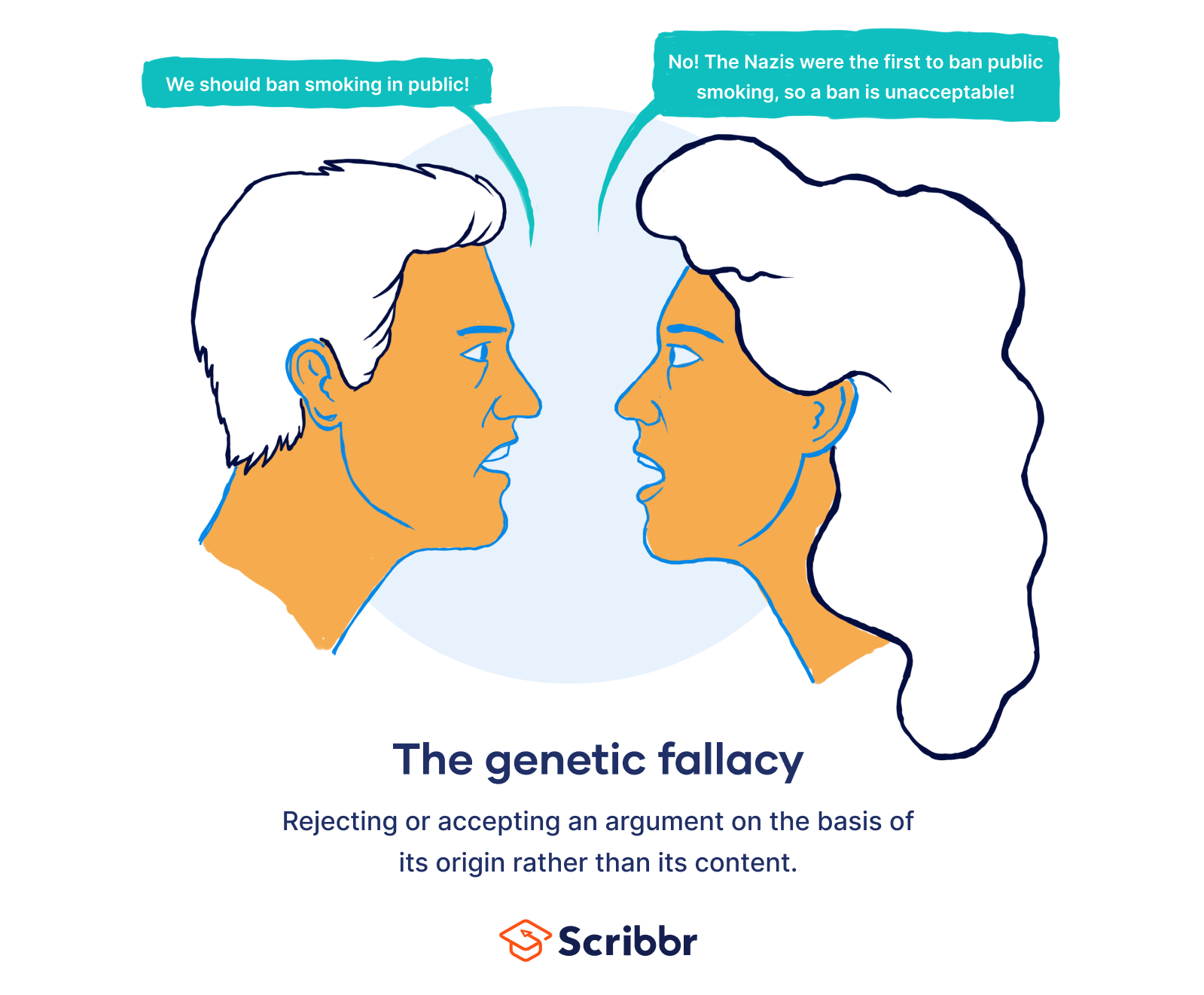

The genetic fallacy is the act of rejecting or accepting an argument on the basis of its origin rather than its content. Under the genetic fallacy, we judge a claim by paying too much attention to its source or history, even though this criticism is irrelevant to the truth of the claim.

As a result, we fail to present a case for why the argument itself lacks merit and to examine the reasons offered for it.

What is the genetic fallacy?

The genetic fallacy occurs when we argue that the origin of a belief, practice, or idea is a sufficient reason for rejecting (or accepting) it. However, the origin or history of an idea has no logical bearing on its truth or plausibility.

In the example above, it may well be that Nazi Germany was the first to impose a smoking ban, but there is also independent scientific evidence that proves the negative impact of smoking on health. In other words, the idea’s origin is irrelevant to the truth of the argument (i.e., that smoking is bad and should be prohibited in public spaces).

Also known as fallacy of virtue or fallacy of origins, the genetic fallacy is an informal logical fallacy where the reasoning error lies in the content rather than the logical structure of the argument. More specifically, it belongs to a group called fallacies of relevance: these are fallacies that appeal to evidence or examples irrelevant to the argument at hand.

Why does the genetic fallacy occur?

The genetic fallacy occurs when we focus on the source or history of an argument instead on the argument itself. This happens because people often confuse:

- Reasons with causes

- Psychological with logical explanations

- The sources with the content of arguments

In other words, we often fail to see the difference between an explanation (i.e., why something is believed) and a justification (why something is true). When reasons for belief are used as though they are reasons for truth, we fall for the genetic fallacy.

When you say this, you are committing a genetic fallacy because you are paying too much attention to how the idea came about rather than to the content of the idea and the justification offered for it (visiting friends, working remotely, etc.).

In general, it’s best to separate the sources from the content of an argument. Even when we perceive the source in a negative (or positive) way, this doesn’t necessarily mean the argument is bad (or good). In other words, we usually can’t prove or disprove a claim by identifying its cause; rather, we need to logically examine the premises and the conclusion.

Why is the genetic fallacy a problem?

The problem in the genetic fallacy is that it fails to engage with the essence of the argument by shifting the focus on something irrelevant (i.e., the origin of the argument).

An argument should be evaluated on its quality—for example, whether the premises are true and logically connected to the conclusion. The origin of a claim cannot prove whether or not the claim is true.

It is important to note that in some cases, the origin of an idea or claim may have a legitimate bearing on how we judge its truth. For example, if we don’t have much firsthand knowledge of a subject, we’re better off trusting a claim about that subject from an expert than one from a layperson.

Genetic fallacy example

The genetic fallacy often arises when someone cites a news story or a specific media outlet that another person doesn’t agree with.

Person 2: I don’t trust this newspaper; it’s controlled by the senator’s opponents.

Here, Person 2 commits a genetic fallacy because they don’t discuss the content of the article itself—e.g., by pointing out weak arguments or a lack of evidence.

The fact that the newspaper is owned by the senator’s political opponents may be true and may be the motive behind the argument the newspaper makes, but it’s not sufficient to disprove the claim (i.e., that the senator has committed high treason).

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about fallacies, research bias, or AI tools, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

AI tools

Fallacies

Frequently asked questions about the genetic fallacy

- What is the difference between the ad hominem fallacy and the genetic fallacy?

-

The ad hominem fallacy and the genetic fallacy are closely related in that they are both fallacies of relevance. In other words, they both involve arguments that use evidence or examples that are not logically related to the argument at hand. However, there is a difference between the two:

- In the ad hominem fallacy, the goal is to discredit the argument by discrediting the person currently making the argument.

- In the genetic fallacy, the goal is to discredit the argument by discrediting the history or origin (i.e., genesis) of an argument.

- What are fallacies of relevance?

-

Fallacies of relevance are a group of fallacies that occur in arguments when the premises are logically irrelevant to the conclusion. Although at first there seems to be a connection between the premise and the conclusion, in reality fallacies of relevance use unrelated forms of appeal.

For example, the genetic fallacy makes an appeal to the source or origin of the claim in an attempt to assert or refute something.

- Why are fallacies misleading?

-

Fallacies are arguments that contain some type of reasoning error. Regardless of whether they are used intentionally or by error, they weaken an argument by using erroneous beliefs, illogical arguments, or deception.

As a result, they shift the focus of a discussion to unrelated topics or side issues and can thus be misleading. For example, the genetic fallacy shifts the attention to the source or origin of an argument instead of presenting evidence to refute the argument itself.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleNikolopoulou, K. (2023, September 08). What Is the Genetic Fallacy? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/fallacies/genetic-fallacy/

Scalambrino, F. (2018). Genetic fallacy. Bad arguments, 160–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119165811.ch29