The Baader–Meinhof Phenomenon Explained

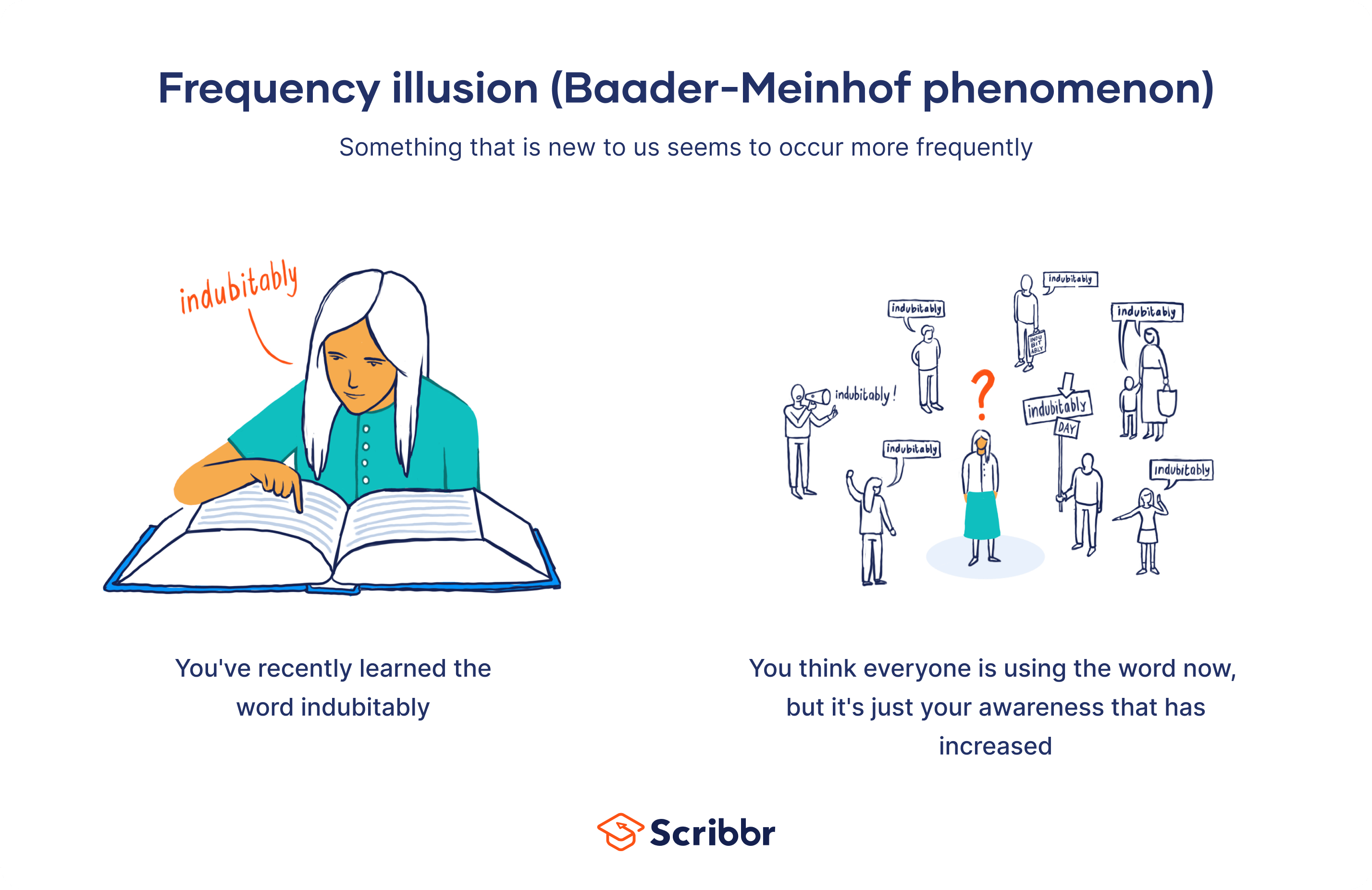

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon refers to the false impression that something happens more frequently than it actually does. This often occurs when we learn something new. Suddenly, this new thing seems to appear more frequently, when in reality it’s only our awareness of it that has increased.

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon is also known as the frequency illusion or recency illusion. While it’s mostly harmless, it can affect our ability to recall events correctly, or cause us to see patterns that aren’t actually there.

What is the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon?

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon is a type of cognitive bias: an error in thinking that occurs while processing and interpreting information. Specifically, it occurs when something you recently learned suddenly seems to appear everywhere.

Whenever we are introduced to new information, such as a new word, we tend to notice it more than we did before. As a result, we may start to think that this new word is present everywhere. Unless that word is currently trending, this is probably due to the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon.

Why does the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon occur?

There are two mechanisms involved in the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon:

Selective attention

Our attention is a limited resource. In our daily lives, we encounter a large quantity of information, but we don’t pay the same amount of attention to every input from our environment. If we did, our brains would be constantly overwhelmed.

In order to be more efficient, our brains allow us to do two things simultaneously:

- Select the most useful information depending on the context or the task at hand

- Disregard all the information that we don’t need

Thanks to selective attention, we can focus on what matters, filtering out less important details. When we learn a new word or set our mind on buying a particular blue car, this information is interesting to us.

For this reason, it stays front and center in our brain for a period of time. This leads us to notice the things that interest us more—i.e., a specific word or car—and ignore the rest.

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias enhances this phenomenon further, by making us look for things in our environment that support our preconceived ideas. For example, if we are seeking encouragement to buy a particular blue car, we seek environmental “proof” that suddenly everyone is driving a blue car.

At the same time, confirmation bias leads us to disregard any information that doesn’t align with those preconceived ideas.

Examples of the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

Because the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon makes us place emphasis on certain aspects of the world arounds us while ignoring others, it can influence our judgment. This can be either positive or negative.

You start reading every journal article you can find on the topic. In this way, you gain an understanding of what to look for when visually examining the upper digestive system of patients, using a process called an endoscopy.

Because this rare disease has caught your attention, you successfully identify two cases that would have gone unnoticed in the next 24 hours after reading the articles.

Here, the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon helped you to detect and diagnose rare diseases by focusing your attention on them.

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon can also mislead scientists.

A similar surge was reported by doctors from different parts of the globe, seeming to coincide with the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. As a result, many doctors concluded that the so-called “COVID toes” were a symptom of the coronavirus infection.

However, in the following months it became clear that the proportion of COVID-infected patients was in fact low among those who had the skin condition. The reason why more people reported skin issues is still being researched.

Doctors were misled by the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon. Because the pandemic was at its peak, it was only natural that some of the patients with swollen toes also tested positive for COVID. This led doctors to perceive an association where there wasn’t one.

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon can inflate the importance of recent stimuli or observations—in this case, people with chilblains who also had a COVID infection.

In other words, after one notices something for the first time (here, the co-presence of COVID and swollen discolored toes), one tends to notice it more often, leading to the belief that it has a high frequency of occurrence.

Other types of research bias

Frequently asked questions

- What are common types of cognitive bias?

-

Cognitive bias is an umbrella term used to describe the different ways in which our beliefs and experiences impact our judgment and decision making. These preconceptions are “mental shortcuts” that help us speed up how we process and make sense of new information.

However, this tendency may lead us to misunderstand events, facts, or other people. Cognitive bias can be a source of research bias.

Some common types of cognitive bias are:

- Anchoring bias

- Framing effect

- Actor–observer bias

- Availability heuristic

- Belief bias

- Confirmation bias

- The halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- Where does the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon’s name come from?

-

The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon is named after a German terrorist group active in the 1970s.

A Minnesota newspaper reader noticed the phenomenon in 1994: one day he was talking with a friend about the group. The next day, he encountered an article in the newspaper mentioning the group, although there was no special reason to expect it would be in the news.

The reader wrote a letter to the newspaper sharing how he became aware of the terrorist group and then read about it soon afterward. This sparked a discussion among other readers who had experienced the same phenomenon, leading to the coining of the term.

- What is selective attention?

-

Selective attention is the process of directing our awareness to something for a period of time while ignoring irrelevant information or any other source of distraction.

Although selective attention makes our thinking more efficient, it can also lead us to filter out important information and distort our perception of the world. The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon is an example of such biased attention.

- What is it called when you learn something and then see it everywhere?

-

This phenomenon is called the Baader–Meinhof phenomenon or the frequency illusion.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

This Scribbr articleNikolopoulou, K. (2024, April 10). The Baader–Meinhof Phenomenon Explained. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-bias/baader-meinhof-phenomenon/

Das, A. (2021). COVID-19 and Dermatology. Indian J Dermatol., 66(3). https://doi.org/10.4103/ijd.ijd_461_21

Kolli, S., Dang-Ho, K. P., Mori, A., & Gurram, K. (2019). The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon of Dieulafoy’s Lesion. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4595