How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples

A results section is where you report the main findings of the data collection and analysis you conducted for your thesis or dissertation. You should report all relevant results concisely and objectively, in a logical order. Don’t include subjective interpretations of why you found these results or what they mean—any evaluation should be saved for the discussion section.

How to write a results section

When conducting research, it’s important to report the results of your study prior to discussing your interpretations of it. This gives your reader a clear idea of exactly what you found and keeps the data itself separate from your subjective analysis.

Here are a few best practices:

- Your results should always be written in the past tense.

- While the length of this section depends on how much data you collected and analyzed, it should be written as concisely as possible.

- Only include results that are directly relevant to answering your research questions. Avoid speculative or interpretative words like “appears” or “implies.”

- If you have other results you’d like to include, consider adding them to an appendix or footnotes.

- Always start out with your broadest results first, and then flow into your more granular (but still relevant) ones. Think of it like a shoe store: first discuss the shoes as a whole, then the sneakers, boots, sandals, etc.

Reporting quantitative research results

If you conducted quantitative research, you’ll likely be working with the results of some sort of statistical analysis.

Your results section should report the results of any statistical tests you used to compare groups or assess relationships between variables. It should also state whether or not each hypothesis was supported.

The most logical way to structure quantitative results is to frame them around your research questions or hypotheses. For each question or hypothesis, share:

- A reminder of the type of analysis you used (e.g., a two-sample t test or simple linear regression). A more detailed description of your analysis should go in your methodology section.

- A concise summary of each relevant result, both positive and negative. This can include any relevant descriptive statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations) as well as inferential statistics (e.g., t scores, degrees of freedom, and p values). Remember, these numbers are often placed in parentheses.

- A brief statement of how each result relates to the question, or whether the hypothesis was supported. You can briefly mention any results that didn’t fit with your expectations and assumptions, but save any speculation on their meaning or consequences for your discussion and conclusion.

If you’re unsure, read the results sections of other papers in your field. This can help you get a clear sense of what information to include.

A note on tables and figures

In quantitative research, it’s often helpful to include visual elements such as graphs, charts, and tables, but only if they are directly relevant to your results. Give these elements clear, descriptive titles and labels so that your reader can easily understand what is being shown. If you want to include any other visual elements that are more tangential in nature, consider adding a figure and table list.

As a rule of thumb:

- Tables are used to communicate exact values, giving a concise overview of various results

- Graphs and charts are used to visualize trends and relationships, giving an at-a-glance illustration of key findings

Don’t forget to also mention any tables and figures you used within the text of your results section. Summarize or elaborate on specific aspects you think your reader should know about rather than merely restating the same numbers already shown.

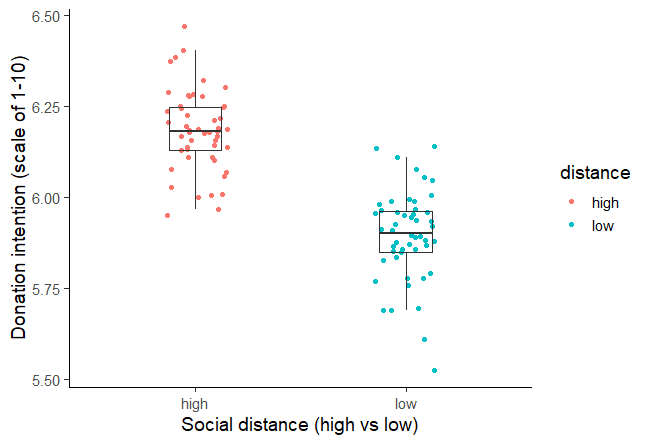

A two-sample t test was used to test the hypothesis that higher social distance from environmental problems would reduce the intent to donate to environmental organizations, with donation intention (recorded as a score from 1 to 10) as the outcome variable and social distance (categorized as either a low or high level of social distance) as the predictor variable.Social distance was found to be positively correlated with donation intention, t(98) = 12.19, p < .001, with the donation intention of the high social distance group 0.28 points higher, on average, than the low social distance group (see figure 1). This contradicts the initial hypothesis that social distance would decrease donation intention, and in fact suggests a small effect in the opposite direction.

Figure 1: Intention to donate to environmental organizations based on social distance from impact of environmental damage.

Reporting qualitative research results

In qualitative research, your results might not all be directly related to specific hypotheses. In this case, you can structure your results section around key themes or topics that emerged from your analysis of the data.

For each theme, start with general observations about what the data showed. You can mention:

- Recurring points of agreement or disagreement

- Patterns and trends

- Particularly significant snippets from individual responses

Next, clarify and support these points with direct quotations. Be sure to report any relevant demographic information about participants. Further information (such as full transcripts, if appropriate) can be included in an appendix.

When asked about video games as a form of art, the respondents tended to believe that video games themselves are not an art form, but agreed that creativity is involved in their production. The criteria used to identify artistic video games included design, story, music, and creative teams.One respondent (male, 24) noted a difference in creativity between popular video game genres:

“I think that in role-playing games, there’s more attention to character design, to world design, because the whole story is important and more attention is paid to certain game elements […] so that perhaps you do need bigger teams of creative experts than in an average shooter or something.”

Responses suggest that video game consumers consider some types of games to have more artistic potential than others.

Results vs. discussion vs. conclusion

Your results section should objectively report your findings, presenting only brief observations in relation to each question, hypothesis, or theme.

It should not speculate about the meaning of the results or attempt to answer your main research question. Detailed interpretation of your results is more suitable for your discussion section, while synthesis of your results into an overall answer to your main research question is best left for your conclusion.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Checklist: Research results

Checklist: Research results

0 / 7Well done!

You've finished writing up your results! Use the other checklists to further improve your thesis.

See all other checklists Return to checklistOther interesting articles

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Frequently asked questions about results sections

- What goes in the results chapter of a dissertation?

-

The results chapter of a thesis or dissertation presents your research results concisely and objectively.

In quantitative research, for each question or hypothesis, state:

- The type of analysis used

- Relevant results in the form of descriptive and inferential statistics

- Whether or not the alternative hypothesis was supported

In qualitative research, for each question or theme, describe:

- Recurring patterns

- Significant or representative individual responses

- Relevant quotations from the data

Don’t interpret or speculate in the results chapter.

- What tense should I write my results in?

-

Results are usually written in the past tense, because they are describing the outcome of completed actions.

- What’s the difference between results and discussion?

-

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research, results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research, it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Results Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/results/